|

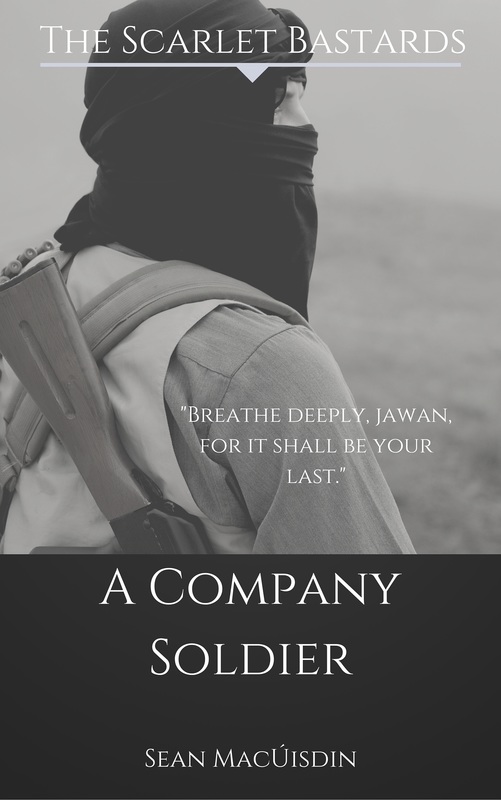

A Company Soldier series - a soldier's memoir set on the colony of Samsara, twenty light years from Earth. Alexander 'Sikunder' Armstrong - a seventeen year old runaway to the United Nations Off-World Legion - faces the grim realty of a hard life on the wild frontier. Surrounded by colourful characters and dangerous enemies in this epic scifi series punctuated by action, humour, and adventure, Sikunder recounts his adventures as a jawan soldier in lavish detail and with an eye to finding the humour in even the most dire of circumstances. I believe it is the true mark of a man’s character in how he faces his end – whether it be a chicken bone in the Savoy Grill, an oncoming Kenworth on the 401, or a Sindhi pirate’s knife pressed to his throat. An imperturbable composure and a ready smile imply both confidence and courage in the face of certain death.

Mind you, being a screamer has its advantages too. I tend to wail as death approaches, and if I’ve grown comfortable with my excitable perturbation, it is because howling like a dervish has staved off my demise on many occasions. Of course in my retired years, as I sip cabernet franc or petite Syrah in my hammock and enjoy the aromatic texture of an Okanagan summer breeze, my thoughts rarely return to the episodic excitations of my youth. Yet on occasion, in between a baked Brie with Amaretto, or a cedar plank salmon, the memories may come back – enduring the biting cold of a Samsāra winter, chopping cords of Pavonis pine for a steamboat boiler, vomiting down the side of a swaying tundra camel, or recoiling in horror at the words of a Sindhi pirate, “Breathe deeply, jawan, for it shall be your last.” If those years in the United Nations Off-World Legion and its host of resident dangers and terrors have forced a certain degree of hysteria to be my mark each time I confront my doom, well, so be it. I may not claim composure as death loomed, but I can at least claim a modicum of success in beating it with each terrible visitation. After all, I’m still alive, ain’t I? Colony of Samsāra, Twenty Light Years from Earth Spring, 2098 I endured three miserable days of post hypersleep sickness following my arrival on Samsāra, the fourth planet orbiting the star, Delta Pavonis, and if you’ve never experienced the heady pleasure of hypersickness, it is characterized by one word: vomiting. Not the normal kind of vomiting that comes with the pastrami in your Reuben Sandwich being a bit off; no, this is the kind of vomiting that comes from mixing tequila with Night Train and a dozen or so Colt 45’s after skipping lunch and supper in preparations for your High School Valentine’s Dance. You can tell I had some experience to prepare me; so, when supine and green in the first few hours after leaving hyperspace, I could at least categorize my torturous suffering and rank it up there with the night I should have gone out with Rachel McMaster but instead ended up lying beside a dumpster with my best friend videoing me and sending it to my mother just to see the look on her face. After a protracted journey over twenty light years in length and through a string of hyperspace jumpgates, boxed up and shipped like a patio set and assigned a similar worth by KlondikeCorp – the bloated corporation chartered to raise, train, and administer the Legion – I and two dozen other like fated souls were dumped by hyper jet in a tiny snow choked spaceport called Menat. Cradled between the rolling hills of the Australus Erebus Vallis and bordered by the indolent slush choked waters of the Enipeus Flumen, Menat and its two hundred or so inhabitants (deposited by an extraordinary degree of moronic planning some one hundred kilometres from the nearest town) lived in an isolated world that would have horrified Odysseus. Pale and nauseous, my nose dripping like a faucet, and terribly conscious of the company I was keeping – refugees to a person from the UN camps in Afghanistan and Kazakhstan – I was herded into the back of a noisome six-wheeled lorry smelling of goat manure and containing, amongst other things, a well-used Persian carpet, four boxes of 9mm ammunition, and eight cages of very displeased chickens. There were six of us squeezed into our lorry bound for a distant cantonment named Ophir Castrum. Two were Han Chinese – young girls named Fong and Kwan I believe, and though I smiled and delivered flimsy, maladroit flirtations (I was seventeen at the time and still dripping with adolescent angst and awkwardness) between wiping my nose on my sleeve or throwing up over the side of the bouncing vehicle, I received little response from either save for a quiet yet very pointed contempt. A third girl and I call her that because she couldn’t have been more than sixteen, was a Kandahar Hindu named Chengelpet, and a prouder more queen-like caricature I hadn’t seen before as she sat beside a pile of manure and brushed off chicken feathers with the grace of a duchess. She was equally disdainful of my chatter, and as the weight of their combined antipathy grew, I quickly lapsed into a sullen silence. My other two companions were of a more menacing nature, a pair of central Asian bandits of foreign character and dangerous repute. One, at sixteen, was a year my junior – a sort of impish Oliver Twist with a Khyber knife and a hashish pipe. The second was in his forties, a hatchet faced brute with a large salt and pepper beard and a glowering countenance. As if faced with a stalking cougar, I avoided eye contact, but allowed a sly surveillance whenever the opportunity presented itself. For twelve wretched hours we endured a penetrating cold that our thin hypersleep coveralls and a pile of mephitic wool blankets did little to protect us from. The ride itself, to make the experience just so much more miserable, was rough and rocking, our road being little more than a trail of stony ruts and slushy puddles that afforded our lorry the bare ability to crawl over its length. On occasion, when we passed some isolated cantonment or a collection of tents that some wag with a sense of hyperbole called a village, we stopped to allow us to disembark and stretch our legs and recover from the beating of the trip. The world that greeted us, a wide river valley between low forested ridges still thick with snow and a brooding ceiling of dark grey cloud that hung at the hilltops, elicited a quiet dread as the desolation of our alien destination intruded. As a young and very sheltered man from the caressing warmth of the Okanagan Valley in the south of British Columbia, the enfolding cold was the first of many unpleasant experiences on Samsāra. What struck me most, however, was the unlikely familiarity of it all. This knowledge was foremost in my mind as I stood on that alien planet twenty light years from Earth. One expected purple skies and indigo grass with seven-legged carnivores festooned with feathers and horns – foolishness of course if I’d bothered to do more than just conduct a cursory read about Samsāra before making the trip. There was, of course, none of that. There was just a wholesome air you could almost drink – crisp and clean; a palatable experience so enjoyable after the aromatic pollution of vineyards, mown grass and spring flowers in the Okanagan. There was still snow on the ground, and mud and rock. Sedge grass grew through the thinning alabaster blanket along with thorny bushes smelling with a faint yet heady mixture of cedar and sage. The trees were tall and slender, with thick scaly bark and massive boughs which spread like a capacious umbrella at their top. They created a dark canopy that allowed ferns, ivy, and lesser bushes to flourish in the frozen gloom. There were very few animals that had been found so far in the twenty years of colonization. Insects abounded including worms – some rather large, snake sized, and apparently quite tasty – and roach and beetle-like creatures that haunted the warmth of sleeping bags and tent corners with their chirps and nibbles. Very much like Earth at first glance, and the impression only grew as our journey continued – an emotional comfort to our cerebral reality. So we carried on through the night, arriving at the cantonment just after dawn the following morning. With the sickening journey finally at an end and every bone and muscle in my body protesting at the ill treatment and, least to say, the growing horror of the situation I had volunteered for three months before in a moment of teenage pique against the smothering machinations of my parents, I lifted the folds of the mildewed cargo bed flap and jumped to the muddy ground. Before me lay the cantonment of Ophir Castrum, and as the sheets of sleet subsided, the glowering dark clouds that had accompanied us since our departure from Menat parted to bathe it in a milky, pallid light. A sorrier looking abode I had never beheld.

0 Comments

|

SerialsThis is my opportunity to share parts of my novels both published and in progress as an opportunity for readers to enfold themselves in the story and characters. I love to write vivid, descriptive narrative harnessing - and sometimes freeing - quirky and unique characters, some of whom have been inspired by historical figures and events. The first book I'll will share is from my military scifi series, The Scarlet bastards. ArchivesCategories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed